My maternal grandma wasn’t a great cook.

Grandma often would beckon guests, whether it be a Saturday afternoon lunch, a Christmas dinner or everyday breakfast with: “Come get a bite to eat.” It didn’t matter how large or small, simple or complex the meal, it was “a bite to eat.” I never saw folks running to her table, though. A solid saunter was about all most could muster.

I’m sure I’ve just committed some type of familial blasphemy. Surely the concept of grandma as a mediocre cook violates some law of nature. You have gravity, the sun rising in the East and grandmas being highly accomplished in the kitchen. Alas, grandma didn’t let anyone starve, but she did not fit the mold of one who turned every raw ingredient into a memorable crave-worthy dish.

My dad dreaded ever having to go to my grandparent’s house to eat. We would cruelly joke while driving to their house for a meal that we would eat as little as possible to be polite and then we’d hit McDonalds on the way home. We never carried through with that plan, but without question, we knew dad was going to be sick after eating grandma’s cooking.

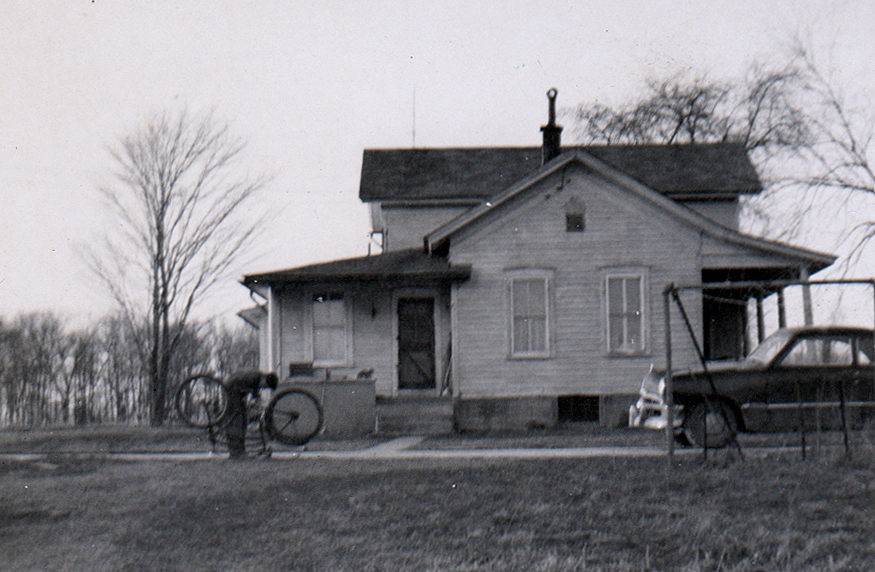

My grandparents were simple country folks. They started their lives together as dairy farmers, but when the farm failed in the late 1950s, they switched to factory and clerical work. Their kitchen was far from clean and almost no sanitary procedures were employed.

A bounty of great vegetables was harvested from their acres of gardens but were compromised by being prepared in unclean conditions, fried in pools of butter that had been lounging, uncovered, hosting flies for months on end. Or cooked with bacon drippings and other animal fats that had been collected over the course of years.

They kept the farmland and during my lifetime the acreage had become hundreds of acres of natural forest. Only two family friends were allowed to hunt on the land and grandpa had one rule for those friends: if you harvest a deer, we want some venison — whatever you think is fair. As a result, the many chest freezers that crowded their breezeway were packed tight with freezer-burned chunks of animal parts. The gamey meat would be butchered in the kitchen, on top of piles of hoarded bread bags and Sunday flyers from the newspaper. It would be served up with floury, fatty, scorched gravy. It was an experience for all the senses.

There were a few winners that slipped through grandma’s kitchen, however. One was what she called chili sauce. I’ve had many chili sauces, and nothing has been a corollary to hers. Grandma’s was rich in tomatoes, not spicy, not sweet, had onions and green bell peppers in it — diced very fine. As with most cooks and an appreciated recipe, she was coy about how the sauce was prepared. Deceptive and evil, even.

One of my cousins in fact was beside herself thrilled when she thought grandma had spilled the beans on that sauce. She soon learned that, when followed, the recipe yielded something more akin to brake fluid than our beloved chili sauce.

One of the simple meals routinely served on the farm was boiled white beans with chili sauce on top. Simple though it was, the big flavors made it a favorite of mine. I never got sick from a meal of beans and chili sauce. I think the tomatoes killed any bugs, crawly or microbial, that may have been present.

For breakfast there often was oatmeal from the “oatmeal pot.” This was a large cast iron dutch oven that hastily would be rinsed between uses but God help anyone who suggested that it actually be cleaned. Breakfasts had been cooked up in that pot since the mid-1930s without it being threatened by soap or a scrubbing pad.

In addition to the aromatics lent by that well-seasoned vessel, grandma would slow-cook the oats with heavy cream, brown sugar, a bit of molasses and raisins. I watched her make it numerous times and I think I make a decent oatmeal, but nothing comes close to my memories. It was just the right consistency (I like my oatmeal on the dry side), chunky and sweet. With some over-buttered toast, it was a great way to get going in the too-early morning hours they kept to. One would have done well to not look inside the pot, however.

Grandma also made a lot of carrot bread. Carrots (and several other crops) grew very well, and they sold them to grocery stores. Her carrot breads were always a little bit burned and tasted more or less okay. But what makes the memory for me is that around the holidays when she’d bake quantities of them, she’d make me my own full-size loaf —without nuts.

She usually loaded the loaves up with walnuts. As a kid I despised nuts of all kinds, so grandma made a special loaf just for me, wrapped in a “recycled” bread bag. She’d put a strip of masking tape on the bag and write “For Aaron” on it so there would be no mistake.

Someone’s cooking, and meals with important people in our lives or around special occasions, certainly can be taken up a level by amazing kitchen execution. But it’s the love, warmth, care, togetherness and thoughtfulness that make a shared meal important and worthy of memories.

Grandma’s cooking was always more than just “a bite to eat.”