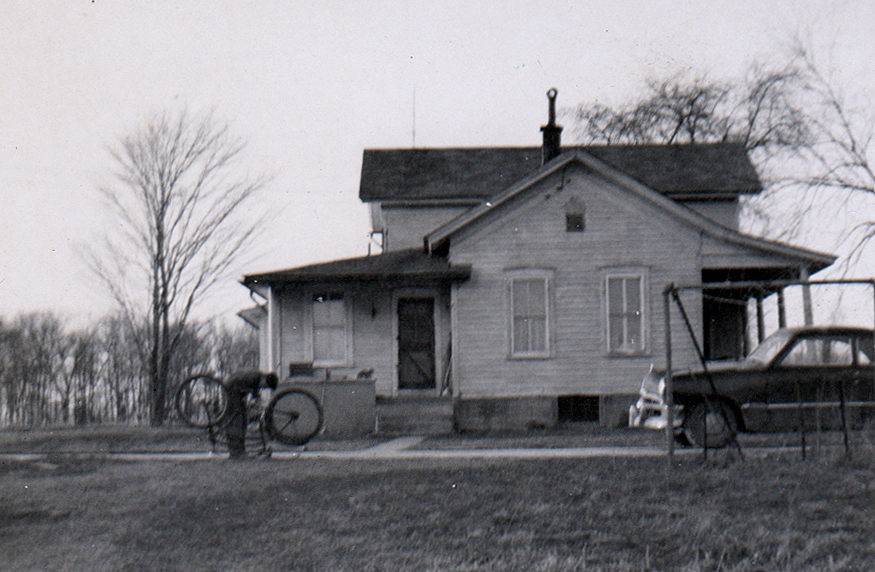

It screamed green. An odd sort of green that was almost kinda-sorta close to the color of the aluminum siding on the house. The outbuilding was a simple structure that could be described as a barn, garage, shed or, for us, the Shop.

The Shop was dad’s refuge to tinker, putter, listen to the radio, make questionable repairs and otherwise make a mess. (Dad’s favorite repair method was two-part epoxy – which got everywhere and had a distinct something’s-dying odor). Dad generally could be found either in the kitchen or the Shop.

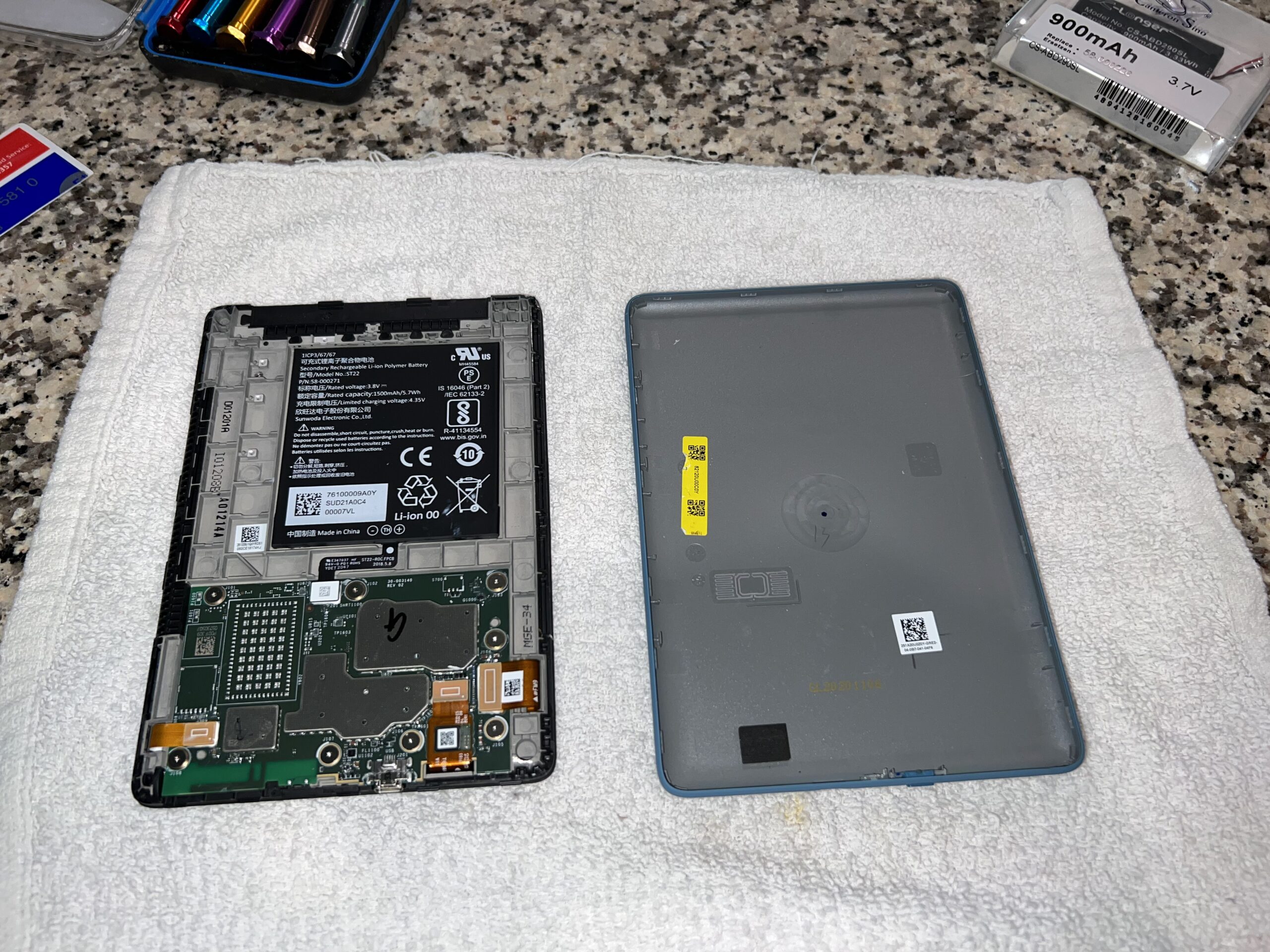

The Shop was also my place. I did my share of tinkering, puttering, listening to the radio and, more often than not, breaking rather than repairing. It was also where I bared my soul to my pets, and occasionally threw a tantrum after being ill-treated by the school bully of the day. It was where I first started fiddling around with wood, tearing down old furniture, electronics and otherwise learning how things worked. Or didn’t after I’d had my way with them.

Dad enjoyed refinishing furniture and I loved hanging out with, and occasionally actually helping, him do the work. Tearing down furniture for refinishing is not only fun, but a learning experience to see how it all works together. National Geographic sure missed out on many amazing photo ops while dad and I practiced our amateur archaeology on bookcases, desks, trunks, boxes and other furniture. Somewhere out there, someone has an old icebox with my small thumbprint in the polyurethane finish – not admissible in court, mind you.

Poorly constructed by any standard, after just a couple of years the Shop started to slouch, sag and sigh on its concrete block foundation. It had a poured concrete floor, but the walls rested on a couple of courses of blocks on grade.

An attic was accessed through a hole in the ceiling. Dad had fashioned a clever rope-and-pully system that would raise and lower a ladder to provide access. The attic was an absolute oven in the summer, and was stashed with “stuff.” Even during my all-too-brief period as a waif child, walking up there could send the entire structure into vibrations, and not those of the Beach Boys variety.

Most of the stuff was absolute junk that long ago should have been converted to cinders and smoke in the burn barrel. But some of it was a great source of diversion for me.

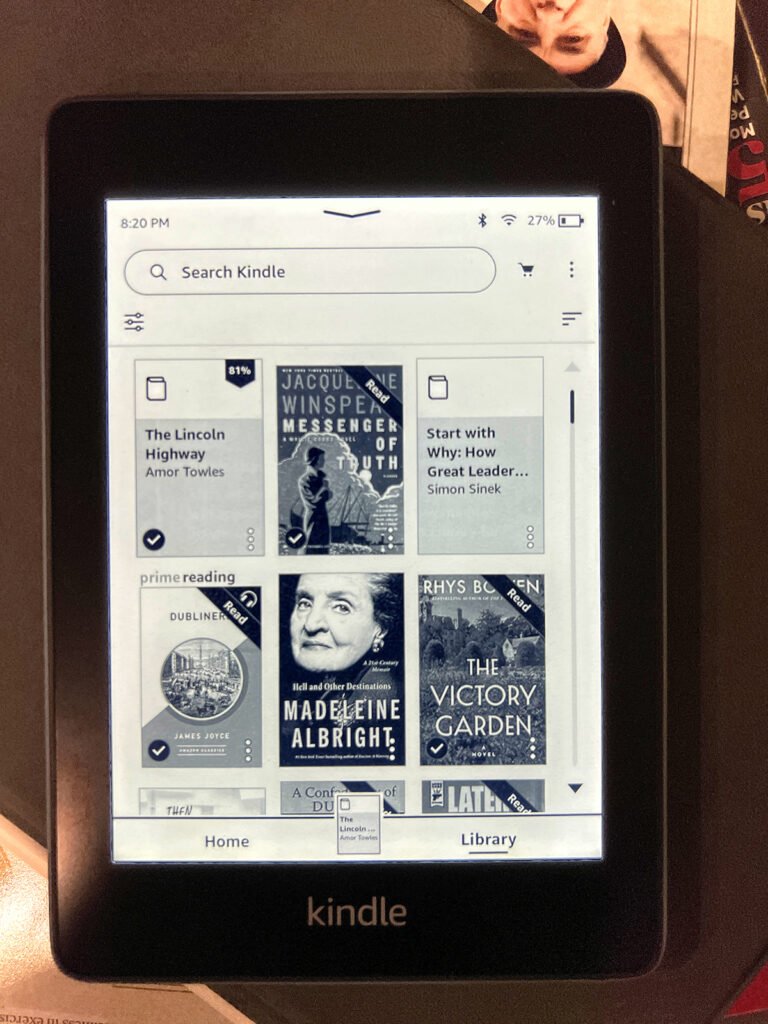

Chief among the attic treasures was dad’s collection of Popular Mechanics magazines. Hundreds of copies from the 1930s through 1960s gave me an accidental education in the history of inventions and technology. To this day I have an appreciation from those issues for how many things we think are “new” really aren’t.

I spent hours in the attic, sitting on the dusty floor that was carpeted with cardboard, reading about competing correspondence schools from the early 20th century that would teach you how to build a radio, tame electricity or work on automobiles. High wages were all but guaranteed if you trained with this correspondence school or the other.

The magazines included inventions of all types, but also plans for building and creating – what we today refer to as Making.

The attic had a westward-facing window that looked out on what dad referred to as our Back 40. We had a total of five acres, but surrounded by farmland there were far more than 40 acres to view – just not under our ownership. At the back of our property was a marsh and forest. From a spot by the window, I could spy on the natural world, the neighboring farmers and their stock, all the while crafting adventures in my head. Most such adventures lead to me grabbing my Daisy Model 99 and heading out to tame the wilds.

For my first few years as a small human person, my parents raised ducks. Part of the Shop was their out-of-the-weather habitat, complete with a little trap door and ramp to allow them to come and go at their pleasure. The Shop also provided sanctuary for our Alaskan Malamute, Iglo. For a while we had a rabbit (very originally named Bugs) who had his own apartment there as well.

Dad puttered with a lot of things, but there always seemed to be some fresh-cut pine from the odd 2×4 giving the place a fantastic aroma. That was combined with odors from the heating stove, the pile of coal, smoke from one of the dozens of Benson & Hedges cigarettes dad would puff through each day, smoldering solder flux and animal essence.

The heating stove remains somewhat of a mystery. I suspect it came from a house – one of those that would lurk in a dirt-and-stone basement, providing gravity heat to the house above. There was no plaque to indicate its maker nor age – but to this little kid, it was certainly first lit up by a T-Rex. It was built like a tank, and we burned coal, wood, scraps of this, that and everything else that got under foot. In the most angry of winters, we easily kept the Shop cozy.

One of my childhood sins was a fascination with fire. I often had free, unsupervised control of the Shop, where I could spray lighter fluid, gasoline or turpentine into the raging fire. And let me tell you, a can of spray paint exploding in the firebox was quite the entertainment for a nine-year-old! I learned a lot of practical lessons about fire, safety and combustibles by risking my life, the Shop and my eyebrows through my experiments.

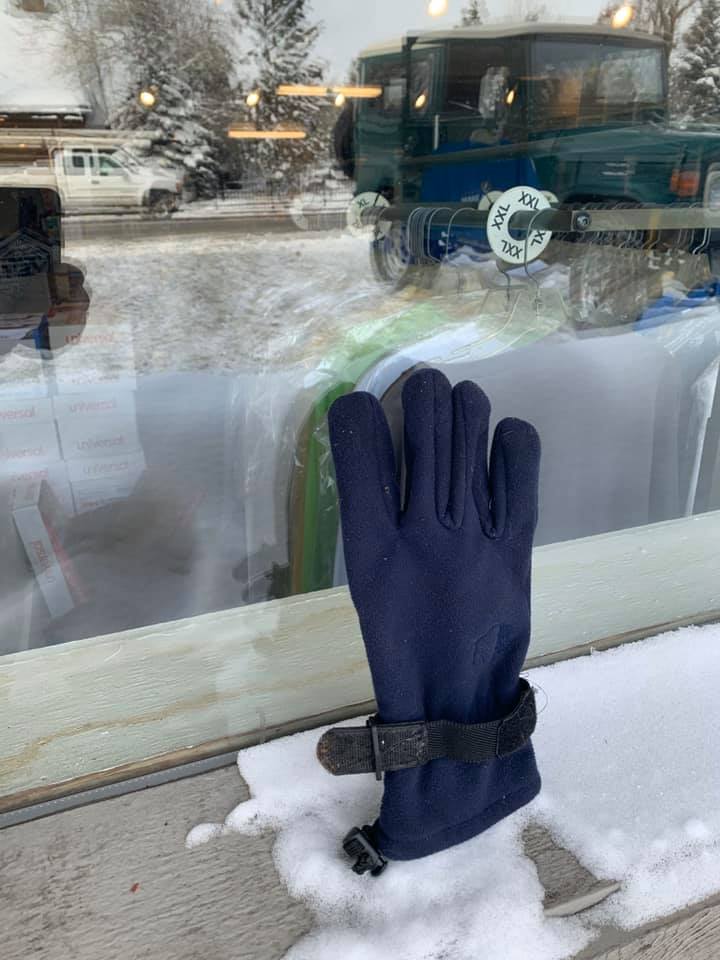

Winter was my favorite time to spend hours in the Shop. A large window allowed me to see storms raging outside while I was cozy in my cabin of fantasy. I would pretend I was having an adventure in a remote, woodland cabin, living off the land, fighting off wild creatures and even wilder outlaws. Whether leaning back in a chair with a stack of old magazines, giving that 99 Champion a good cleaning or inserting a bunch of holes in some tin cans, my dog and I in the shed was my small Heaven.

You might think that some eating and drinking took place in the Shop, but no, not really. The one exception was dad’s not-so-secret stash of Brach’s square caramel candies. The candies were kept in a fancy glass jar with a tight-fitting lid. The jar was on the highest shelf possible, hugging the ceiling, along with tools, doodads, fittings and ephemera that were rarely used. Even at six feet tall, dad needed to stand on something to grab a caramel. When I was on my own, I’d have to climb up onto the workbench and then employ the tippy-toe method to get a square.

In the summer they would soften and occasionally become a gooey mess – requiring us to scoop out chunks of caramel and eat them, just to clean up the jar. We just had to do it – there was no other way. In the winter they froze into jaw-testing square boulders. I only remember one time when the jar went empty. When dad took that last candy, whatever his agenda was for the day, it got changed on the spot! We hopped in the truck and headed to the grocery to the Brach’s Pick-A-Mix contraption to fill a bag to bursting with a fresh supply. We of course would each test one in the store, to make sure there had not been a quality-control lapse at Brach’s Caramel Central. Then, on the 2-½-mile trek back home, we’d need to have a couple more caramels to keep up our strength.

Hanging on the wall by the sliding entry door was a telephone, an extension from the house. With a unique sequence of numbers, we could actually dial into the house: “Mom, can we get pizza for dinner tonight?” In addition, being on a party line, the Shop provided a youthful spy-in-training the perfect covert location from which to listen in on the conversations of our neighbors. I still can’t believe that Merris planted her carrots in the same field as last year’s beefsteaks.

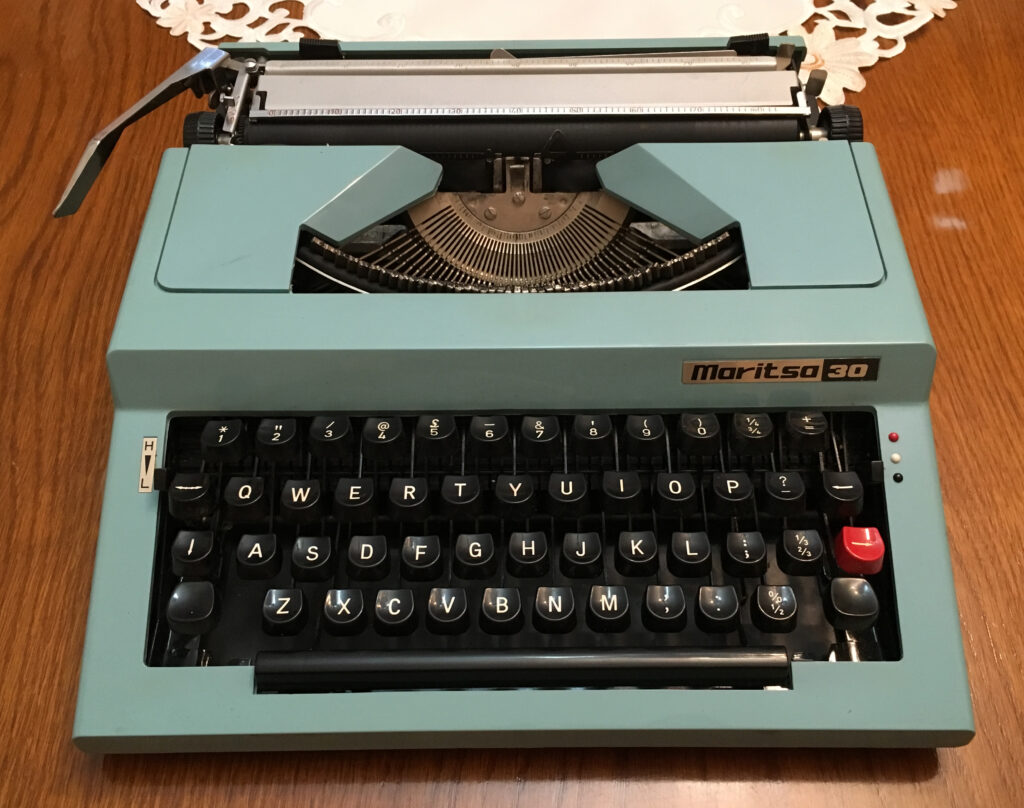

A couple of shelves below the Brach’s jar sat a radio. An early 1950s Admiral AM radio with clock, it often would be playing in the background. Filthy beyond recognition, filled with sawdust and other detritus, the radio nonetheless pulled in WKZO 590 from nearby Kalamazoo, as well as WBBM and WMAQ from across Lake Michigan in Chicago.

Neither dad nor I were sports fans, but I remember listening to the Detroit Tigers and Chicago teams having their games called on that radio.

Being a tube set, those tubes could get blazing hot, at which point the radio would stop working. The sudden silence made the space feel creepy and lonely. Today, all cleaned up, the radio still works. Though, like me most mornings, it needs some time to warm up.

Through every stage of my adult life, I’ve longed for an outbuilding of some sort for my woodworking hobby. A place not connected to the house where I can create my own cozy, pine-scented, varnish-vapor memories. But those memories from long ago – time spent with my dad and time spent chasing my own imaginations – remain with me, one of the many elements of my own foundation, hopefully a little more stable than a couple of courses of concrete blocks.