Today I am thinking of one of my teachers. Jim Grossa was my high school shop teacher. I don’t know what brought him to mind today in particular, but he left some marks on my squishy and aimless 14-year-old-noggin that are with me to this day.

Today I am thinking of one of my teachers. Jim Grossa was my high school shop teacher. I don’t know what brought him to mind today in particular, but he left some marks on my squishy and aimless 14-year-old-noggin that are with me to this day.

Mr. Grossa had a degree in Industrial Arts and in my general shop class taught woodworking and metalworking. I of course took the class because I was interested in woodworking. Though I ended up enjoying the metalworking as well, very much to my surprise. For a while I thought a career operating a spot welder would be just the ticket!

The This Old House TV show had just started, but our 30-foot TV aerial rarely was able to pull it in. I had seen a couple of episodes in other people’s houses and was fascinated to see “how” woodworking was done.

The only real exposure I had to seeing woodworking done was the occasional Shopsmith demonstration held at the local mall.

The opportunity to get into an actual woodshop and learn how to make things with wood was really exciting. And in the tiny, poor rural school in Gobles, Michigan, we actually had an excellent shop with good tools.

And a great teacher in Mr. Grossa.

Years temper the memories and my recollection may not be 100%. But I remember the lessons that have stuck with me all of the intervening years.

I remember on the first day of class, comprised almost totally of boys, rowdiness was the order of the day. Grossa (for some reason we rarely used the title Mister – he was just “Grossa”) shouted “Settle down!” over the commotion. He was a tall, thin man, probably not a whole lot older than us, with what would later be known as a Magnum P.I. mustache. The girls thought him handsome and often would stop to watch him walk away down the halls.

He went on to say that he knew some were in the class for an “easy-A” and others were there because they wanted to learn something. “Those of you who want to coast can do that, but be quiet and stay out of the way so those who want to learn can learn and so you don’t get hurt.”

I was in the “I want to learn something” camp.

One of our first lessons, before we were ever turned loose in the shop, was on how to measure.

It may sound way too fundamental, but it’s really important, and Grossa built upon this throughout the semester. But it’s where I had a real problem. Okay, I continue to have a real problem. To this day I have a devil of a time reading a ruler or tape measure.

I pretty easily understood that inches were broken down into quarters, eighths, sixteenths, thirty-seconds and so on. I got that. But seeing and counting those tick marks is a real challenge for me. I have to close one eye, squint with the other, and somehow point to and count the ticks to get a measurement. It sometimes helps if I lift my right foot off the ground and hum the theme to Gilligan’s Island.

Working in my own shop as an adult, I can take my time, do it three, four or eighteen times. But in class, under pressure, I sweated.

My completed checkerboard from shop class.

We had prescribed objects and projects that we had to make. One was a checkerboard. I remember Grossa showing us a sample of what we were going to make and I was terrified. I couldn’t imagine how even to start such a project and was afraid I’d flounder and fail.

But I likewise remember as the lightbulbs began to light up when he showed us the process. It all made sense!

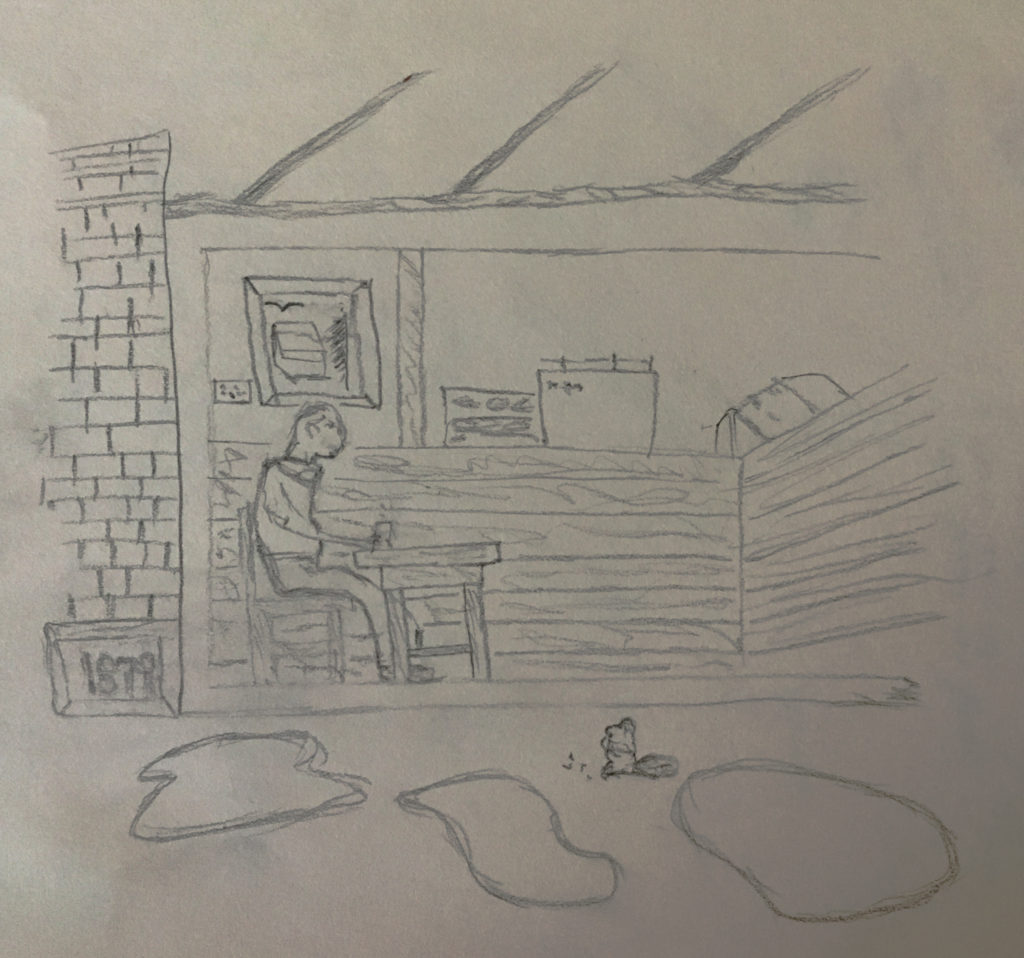

One of the things Grossa taught me on that project was the value of a plan. To this day when I plan a project, it’s sketchy at best. I once took a drawing class at D’Art Center in Norfolk, VA to try to learn a thing or two so I could make better drawings for myself. I had fun and a helpful teacher, but it didn’t stick. My plans continue to be things only I can understand.

At any rate, Grossa said that any project we might want to tackle came down to a plan. Whether it was someone else’s plan or one of our own, the largest, most complex of projects came down to one cut at a time. True with woodworking or any other project or task in life.

Break it down he said, on paper and in your head, into steps small enough to understand and complete. You don’t build the entire project, you build it piece-by-piece.

At my age, that really was profound. And prior to woodshop someone could have used those same words to describe a process, but because it was something I was interested in, and making things with wood was something I truly wanted to master, it made sense, made an impression. It was a lesson made practical.

Having watched several of those Shopsmith demos in the mall, I was the most fascinated by the lathe. I have never been interested in carving, but turning something on the lathe is magical.

My completed bowl from shop class.

There wasn’t time in the class to get very good at the lathe, but I did learn the basics of how the machine worked, how to mount my work (this was before four-jawed chucks came to the world of woodworking – greatly simplifying and speeding up the process of turning wood). I learned about the major lathe chisels and types of cuts.

My lathe was positioned such that I looked out a large west-facing window. I had a view of the woods beyond and truly enjoyed spinning poor dead tree pieces to dust. I ended up making a really awful bowl.

Part of the problem was that my choice of wood was bad. It had lots of open end-grain so no matter what I did, I couldn’t get it smooth. While I wasn’t proud of the project, like I was the chessboard, I cherished it.

The final project for woodshop was a project of our choice. We had to submit the idea and a sketch and get approval from Grossa before beginning work.

Students submitted proposals for toolboxes, bird feeders and bird houses, cutting boards – the types of beginner projects you’d expect.

This is sort of what the loop would have looked like, hanging from a central post.

But my idea was wildly different. I had seen a towel rack that I wanted to make in a store. This rack was intended to hold hand towels in a bathroom. It had a central square post of about 1-1/2” square. On each of the four sides there was a smooth circle with an “arm” that was let into the main post. Hard to imagine what I’m talking about, eh? Well, it is hard to describe. And I drew crude drawings on paper and on the chalkboard to try and explain what the “thing” I wanted to make was.

Grossa was clearly lost – he didn’t understand what I wanted to build. But everything I described sounded like too challenging a project for my skill level. I was insistent that I wanted to make it and Grossa was honest with me: he didn’t fully understand it, he wouldn’t have enough time to really help me refine it; and I needed to “complete” my project in order to complete the class and be graded.

But bit-by-bit, the project evolved. He let me use some really excellent cherry wood from the inventory. Every time I work with cherry, I think of that towel rack. Cherry is beautiful wood, changes color over time and is great to work with.

Grossa regularly consulted with me. And as he’d taught, I had broken the project down into steps. And while he didn’t understand what I saw in my head, he could understand each of my small steps and thus help me to do them.

My project required four mortices to be cut into that main post. A mortice is a fairly advanced cut and, except for identifying it, was not covered in the class. But Grossa spent time with me to show me how to attach morticing chisels to the drill press, how to mark out the cuts, make and refine them with hand chisels.

It was a lot of hard work but in the end my mortices were actually pretty good.

The central post needed some kind of legs to hold it upright. We came up with simple legs with two 45-degree angles cut on them. One angle would sit against the post, the other against the floor. For the sake of time, Grossa suggested I screw them to the post, create counter-sinks and make my own plugs to fill the counter-sinks.

What was he thinking? Heck, what was he saying?! Countersink? Plugs? But he showed me each new process, often doing one and then setting me free to do the rest.

I suppose the fact that he’d show or tell me something and then “leave me to it” was a necessity of helping as many students as possible. But at the time I saw it as his confidence in me. He didn’t need to stand over me. He believed I could do a process, so he could move on to someone else. As a shy kid lacking in anything that looked like confidence, that meant a lot to me.

I’m sure my parents were sick and tired of my regular praise of Mr. Grossa and all of things he knew!

The next challenge was to make the rings that would actually hold the towels. It required a single piece of wood with a round outside, a hole cut from the center and a “tail” that would fit into the mortice cut in the main post.

Again, a lot of sophisticated cuts to make. And again, Grossa helped me with each step. I probably used every tool in the shop to get those things cut. And it took forever. I got right down to the wire and never did the proper finishing. But Grossa encouraged me to finish – do what was required for the class. I could make it prettier on my own at home – he said he was confident I had learned enough to continue.

His confidence in me meant so much! He knew it was important to me and he just assumed I’d keep going on my own, during the summer and in years to come. It wasn’t just about him doing his job for a semester – he was coaching and encouraging me to use and develop a skill and hobby for the rest of my life. He surely was a great success with that.

I completed the project, though it wasn’t finished. I sheepishly took it home on the school bus at the end of the semester. I was embarrassed by it, but proud at the same time. I knew that people looked at that weird contraption and tried to say nice things, or teased me or whatever they would do. But when I looked at it I was proud of what I’d learned.

I had learned how to measure something, rough out raw stock, cut multiple items to the same dimensions, cut mortices, use the jigsaw, tablesaw, sanders, drill press, morticing chisels, hand chisels. So many skills and tools were now real world experiences for me – not dreams or magazine articles. A few months before it had all been unknown and mysterious. But Grossa led me to pursue my passion, and learn things without knowing I was learning them!

I made a lot of mistakes on that towel rack. I got frustrated. Pieces had to be discarded. I had to stop and start. I used some fancy language. But this is where Gross taught me perhaps the most-important thing. I have used this lesson throughout my life for so many things – most of which have nothing to do with woodworking.

When I’d make a mistake and get frustrated he’d tell me that it wasn’t a failure, it was a prototype. A failure was just a lesson, evidence of something you learned. You’d try again, taking what you’d learned from the “prototype”, make changes, maybe make more “prototypes”, but get better each time.

I still got frustrated and upset over my mistakes, but I quickly saw how true his words were! I tried to look at what went wrong, figure out why it went wrong and what I could do to start again. He was always so calm, friendly and positive. He didn’t hover or mother in any way, but I knew he supported me and had confidence in me…which helped me to build a little bit in myself.

Over the years I’ve taken classes and gone to specialty schools for a variety of woodworking skills. I’ve learned about cabinetmaking, woodturning, hand-cut joints, router techniques, finishing. And I’ve built out my own workshop and made hundreds of projects with wood. Without the skills and confidence gained from Mr. Grossa, there is no doubt: I wouldn’t have taken even the first step.

I always want to make nicer projects, more complicated work, items with fewer flaws and errors. But I enjoy the process, I enjoy what I learn from each project. And I have used the lessons and example of Mr. Grossa, my shop teacher, who taught me so much more than measure twice, cut once.

Some examples of the many things I’ve made with wood, thanks to a start from Mr. Grossa. No pictures of prototypes here, just evidence of lessons-learned.

I generally make a pot of coffee in the morning. I am not particularly loyal to a roast, but tend towards Starbucks or Seattle’s Best brands. Sometimes, if the package is pretty and the price low, I’ll try something else.

I generally make a pot of coffee in the morning. I am not particularly loyal to a roast, but tend towards Starbucks or Seattle’s Best brands. Sometimes, if the package is pretty and the price low, I’ll try something else.